Arboviral infections

Arboviral infections are caused by arbovirus transmitted by certain types of blood-feeding arthropods.

Last updated on 07 October 2025

In brief

- Arboviral infections are caused by arboviruses, which are virus transmitted to humans and/or other vertebrates by certain types of blood-feeding arthropods (mosquitoes, ticks, sandflies and midges).

- Blood-feeding arthropods transmit the pathogen during their blood meal, after having bitten an infected person or animal.

- Dengue, Zika and chikungunya are some of these arboviral diseases.

Origin of arboviral infections

Vector-borne diseases are are human diseases caused by parasites, viruses, or bacteria transmitted by vectors.1

Among these, arboviral infections are transmitted by biting arthropods (mosquitoes, ticks, sand flies, or culicoides). 2 There are more than 500 recognized worldwide, 150 of which affect humans.3 Those with the highest prevalence are dengue (96 million cases per year), Chikungunya (693,000 cases per year), Zika (500,000 cases per year), yellow fever (130,000 cases per year), Japanese encephalitis (42,500 cases per year), and West Nile virus (2,588 cases per year).4

History

Human populations were relatively isolated from each other for long periods, protecting them more or less from epidemics. The first extensive mass migrations, such as the slave trade, which decimated indigenous communities, exacerbated the spread of pathogens on a large scale. 5 The globalization of pathogens, initiated by regional and global conflicts, has increased with the development of rapid modes of transportation, particularly aviation, the emergence of trade and travels, and climate change.5,6

These favorable conditions have enabled the development of anthropophilic mosquitoes and the emergence of arboviruses. The geographical distribution of arboviral diseases is now expanding beyond their natural limits and reaching new regions that had previously been spared.6

According to the WHO, these trends are expected to continue as the climate continues to get warmer.1

Before 1930, half a dozen arboviruses had been isolated. By 1940, around ten additional viruses were known. Between 1950 and 1979, the list grew to include 460 new viruses. In the 2000s, the number of known arboviruses remained stable at around 530 or 540.7

Research has shown little interest in arboviruses except during health crises.7,8 However, the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has changed the game.8

Arboviruses circulate mainly in tropical or subtropical regions. However, over the past few years, an increase in the description of indigenous cases has been reported in temperate regions, such as mainland France and other European countries. Arboviruses include approximately 500 viruses, about one hundred of which are pathogenic to humans. They belong to different genera, such as Flavivirus (yellow fever, dengue, Zika, Usutu, West Nile, tick-borne encephalitis, etc.) or Alphavirus (chikungunya). Some arboviruses cause viral haemorrhagic fevers (Rift Valley fever, Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever, etc.).

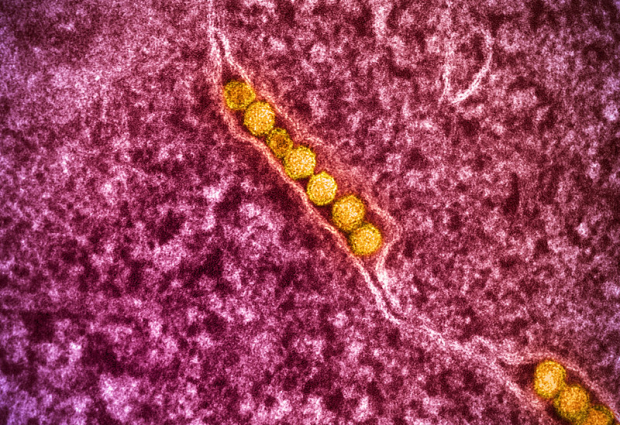

Arbovirus

From a taxonomic point of view, arboviruses (for Arthropod-borne viruses) are very different from each other. However, they share a common transmission cycle involving two hosts: a vertebrate and a blood-feeding arthropod vector (mosquitoes, ticks, sand flies, or culicoides) in which the virus replicates, infects the digestive tract and then the salivary glands.5,7 They are mainly RNA viruses.9

The current classification is virological. Nearly two-thirds of arboviruses are divided into three families:2,7

- Togaviridae, including 28 viruses, 17 of which are pathogenic (chikungunya)

- Flaviviridae, with 68 viruses, 38 of which are pathogenic (dengue, West Nile virus, yellow fever, Zika)

- Bunyaviridae, with 252 viruses, 64 of which are pathogenic (Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever virus)

Nearly 28% of arboviruses belong to two other families (Reoviridae and Rhabdoviridae), and less than 6% are found in various other families.7

Transmission

The passage of the virus from the infected arthropod to the vertebrate host is horizontal transmission (as opposed to vertical transmission, which is the passage of the virus from the infected female to her offspring). This mechanism ensures the active circulation of the virus in epidemic situations.5 Mosquitoes are the most common vectors.6

Aedes mosquitoes are vectors of dengue virus (DENV), chikungunya virus (CHIKV), yellow fever virus, and Zika virus (ZIKV). Anopheles mosquitoes are the primary vectors of the Plasmodium parasite, which causes malaria. Culex mosquitoes transmit Japanese encephalitis virus and West Nile virus.1,6

Most arboviruses originally circulate in a “wild environment” among wild animals (including non-human primates), which act as reservoirs, and zoophilic mosquitoes (enzootic cycle).5

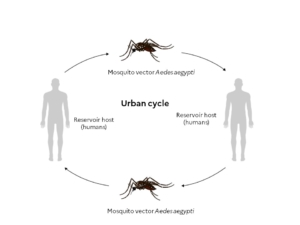

Arbovirus emergence in humans results from the virus transitioning from a wild cycle to an urban cycle. This is maintained by anthropophilic mosquitoes, which transmit the virus from animals to vertebrate hosts, i.e., humans (zoonosis). 5 The emergence is linked to the infection of an anthropophilic-zoophilic mosquito by a wild virus, with the mosquito acting as a bridge vector between the animal and humans.5 The main urban epidemic vectors are Aedes aegypti and Ae. albopictus.5

However, some arboviruses do not need to be amplified in animals to be transmitted to humans. Humans are therefore reservoirs, amplifying hosts, and disseminating hosts,6 which gives these arboviruses significant epidemic potential.10 Dengue, chikungunya, and Zika are examples of this type of arbovirus disease.6,10

Global travel and trade, unplanned urbanization, mainly in large tropical cities, and climate change are key drivers of anthropophilic mosquitoe development and arboviruse emergence. 6 This context favours the emergence or re-emergence of certain infectious diseases in previously unaffected geographical areas, with tropical countries being particularly affected.1,6

Symptoms and treatment

Symptoms

Variation in the virulence of arboviruses observed among epidemics, depending on when they occur and where they are located.11 It also depends on:11

- The host’ immune status and immune response to viral infection, which is influenced by genetic factors

- The viral structure

The immune response to infection is essential in symptoms of viral infections.11

Many arboviruses cause subclinical infection, detected only by the presence of antibodies11: 80% of infections are asymptomatic and 20% cause flu-like syndromes, often associated with a rash.12 Severe forms can cause pulmonary, neurological or haemorrhagic syndromes.11,12 These forms, about 1% of infections, vary depending on the virus and its cellular tropism.12

Certain signs are more characteristic of a particular arboviral infection: the absence of fever and conjunctivitis for Zika virus infection, leukopenia and thrombocytopenia for dengue, and intense arthralgia for chikungunya.10

Some arboviruses leading to encephalitis syndrome, such as West Nile virus, can cause lesions often irreversible and sometimes fatal. 11 This syndrome is characterised by a sudden onset of fever, vomiting, neck stiffness, dizziness, drowsiness, disorientation, followed by confusion, and progression to stupor and coma.11

Treatment

There is currently no specific antiviral treatment.13 Only symptomatic treatments are available.13

Diagnostic

Fever is commonly observed in malaria, typhoid fever, rickettsiosis, leptospirosis or primary HIV infection.10 Arbovirus infection is suspected only if symptoms began no later than two weeks (usually two to eight days) after returning from an endemic region, particularly in cases of skin rash, muscle and joint pain.10

RT-PCR testing must be conducted within five days of the onset of clinical signs. Specific IgG and IgM serology testing is indicated from the fifth day after clinical sign onset.12

Prevention

Vector control

Vector control measures remain critical for prevention. The most common approaches are the use of larvicides directly applicated to stagnant water or spraying insecticide to kill adult mosquitoes.13 However, insect vectors capable of resisting insecticides have emerged, undermining prevention strategies.6

Other more experimental approaches are being used, such as releasing Aedes aegypti mosquitoes whose ability to transmit viruses to humans has been reduced by infecting them with Wolbachia bacteria. 13 Breeding of these infected mosquitoes with the wild mosquito population ultimately reduces the number of mosquitoes that are efficient vectors.13 Another approach is releasing large numbers of sterile male mosquitoes to mate with females in the wild to reduce their fertility.13

Individual protection measures include mosquito repellents, wearing long, loose-fitting clothing, insecticides, chemical repellents, installing mosquito nets to prevent mosquitoes from entering a space, and mosquito traps.14

Vaccines

Vaccines are one of the preventive measures against arboviruses. Available vaccines are used to prevent dengue and chikungunya.13

Research: The actions of ANRS MIE

ANRS MIE research priorities

Placed under the aegis of ANRS MIE, Arbo-France is a French multidisciplinary and multi-institutional network for monitoring, surveillance and research on human and animal arboviruses in mainland France and its overseas territories.

To learn more about research areas and projects, consult the fact sheets on the virus you are interested in:

References

- Vector-borne diseases. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/vector-borne-diseases (Consulté le 02/07/2025)

- Girard MP. Arboviroses et fièvres hémorragiques : actualités épidémiologique et vaccinale. Bull Acad Natle Méd 2016 ; 200 (8-9) : 1617-1630

- Madewell ZJ. Arboviruses and their vectors. South Med J 2020;113(10):520-523

- Franklinos LHV, et al. The effect of global change on mosquito-borne disease. Lancet Infect Dis 2019;19: e302–12

- Failloux A-B. Les moustiques vecteurs d’arbovirus : une histoire sans fin. Biologie Aujourd’hui 2018 ; 212 (3-4) : 89-99

- Failloux A-B. Les émergences d’arboviroses : Chikungunya et zika. Bull Acad Natle Méd 2016 ; 200 (8-9) : 1589-1603

- Chippaux A. Généralités sur arbovirus et arboviroses. Médecine et maladies infectieuses 2003 ; 33 (2003) : 377–384

- Arbo-France, ANRS MIE. Stratégie de la recherche sur les arboviroses humaines et animales, 2023. https://arbo-france.fr/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Document-strat%C3%A9gie-Arbo-France-20230131.pdf (Consulté le 02/07/2025)

- Ciota AT, Kramer LD. Insights into Arbovirus evolution and adaptation from experimental studies. Viruses 2010;2:2594-2617

- Schaller A, et al. Arboviroses émergentes : quelle démarche diagnostique chez les voyageurs ? Rev Med Suisse 2016 ; 12 : 889-94

- Deubel V, Georges-Courbot M-C. Les arbovirus et les virus épizootiques. C. R. Biologies 2002 ; 325 : 855–861

- Durand GA, et al. Les arbovirus en France métropolitaine : diagnostic et actualités épidémiologiques. Revue francophone des laboratoires 2021 ; 529 : 49-57

- Neyts J. Challenges in combating arboviral infections. Nat Commun 2024;15(1):3350

- Wilder-Smith A, et al. Epidemic arboviral diseases: priorities for research and public health. Lancet Infect Dis 2017;17(3):e101-e106

ANRS MIE Arbovirus news

PEPR MIE – Publication of the booklet about the 2023-2025 laureates and junior chairs

Overview of the 34 research projects and junior chairs funded by France 2030’s PEPR MIE programme.

02 March 2026