Dengue

Dengue is an infectious disease caused by the dengue virus, an arbovirus. It is the most widespread human arboviral disease in the world.

Last updated on 07 October 2025

In brief

- Dengue is an infectious disease caused by the dengue virus, an arbovirus.

- Around half the world’s population is now thought to be at risk of this virus transmitted by infected mosquitoes.1

- It is the most widespread human arboviral disease in the world.2

Origin of dengue

History

Dengue is found mainly in the tropical and subtropical regions of the world.1,2 Its incidence has increased significantly in the space of a few decades: from 505 430 cases in 2000, the number of cases reported to the WHO peaked in 2023 with more than 6.5 million cases and over 7 300 related deaths.1 As at 30 November 2024, more than 14 million cases of dengue had been reported since January of the same year, including over 10 000 deaths.3

In 2019, the report of The Lancet Countdown on health and climate change found the spread of dengue to have been encouraged by recent climate changes occurring since the 2000s.4 Its spread around the world has been rapid. The continent most affected is Asia – considered the cradle of the dengue virus, followed by the Americas – where the number of cases has risen sharply in recent years, and then Africa.2,5,6

By 2024, there was active dengue transmission in 90 countries. The disease also affects the eastern Mediterranean, the western Pacific, and is spreading to new regions of Europe.1

Between 2010 and 2023, a total of 273 indigenous cases were recorded in Europe. In mainland France, two cases of local transmission were reported for the first time in 2010.7 In 2023, an indigenous dengue outbreak involving three cases was identified for the first time in Île-de-France8 and, since 1 January 2024, over 1 679 dengue cases have been imported into mainland France compared with 131 over the same period in 2023.9

It has been estimated that 390 million dengue virus infections occur annually worldwide, 96 million of which manifest clinically.1 The 2023 edition of the Lancet report estimates that dengue transmission could surge by 36% by the year 2050.10

The dengue virus

The dengue virus is an RNA virus belonging to the Flaviviridae family and the Flavivirus2 genus. It is classified into four distinct serotypes: DENV-1 to DENV-4.2 This difference does not confer long-term cross-protection: recovery after infection results in lifelong immunity against the serotype causing the infection, but not against the other three.2

Transmission

Mosquito bite transmission

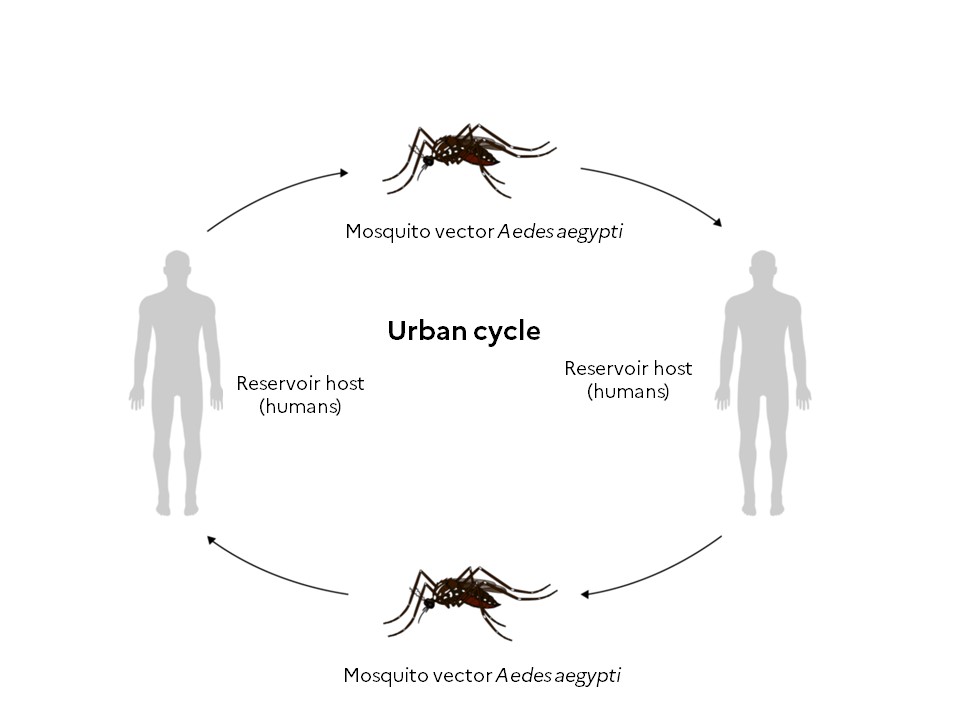

The transmission of dengue follows two cycles: a sylvatic cycle in forest areas during which the virus circulates between non-human primates and mosquitoes of the genus Aedes (Aedes luteocephalus and Aedes furcifer), and an urban cycle in which the virus circulates between humans and urban mosquitoes (Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus).2

Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes move little during their lifetime. The females lay their eggs at sites where the presence of stagnant water is necessary for larval development.11 After feeding on the blood of an infected person – while most people are viraemic for around 5 days, viraemia can last as long as 12 days – the virus replicates in the female mosquito’s midgut before disseminating to its salivary glands.1,2 It takes around 10 days for the virus to multiply within the mosquito1. Following this period, the infectious mosquito can transmit the virus and infect a new person.1,11

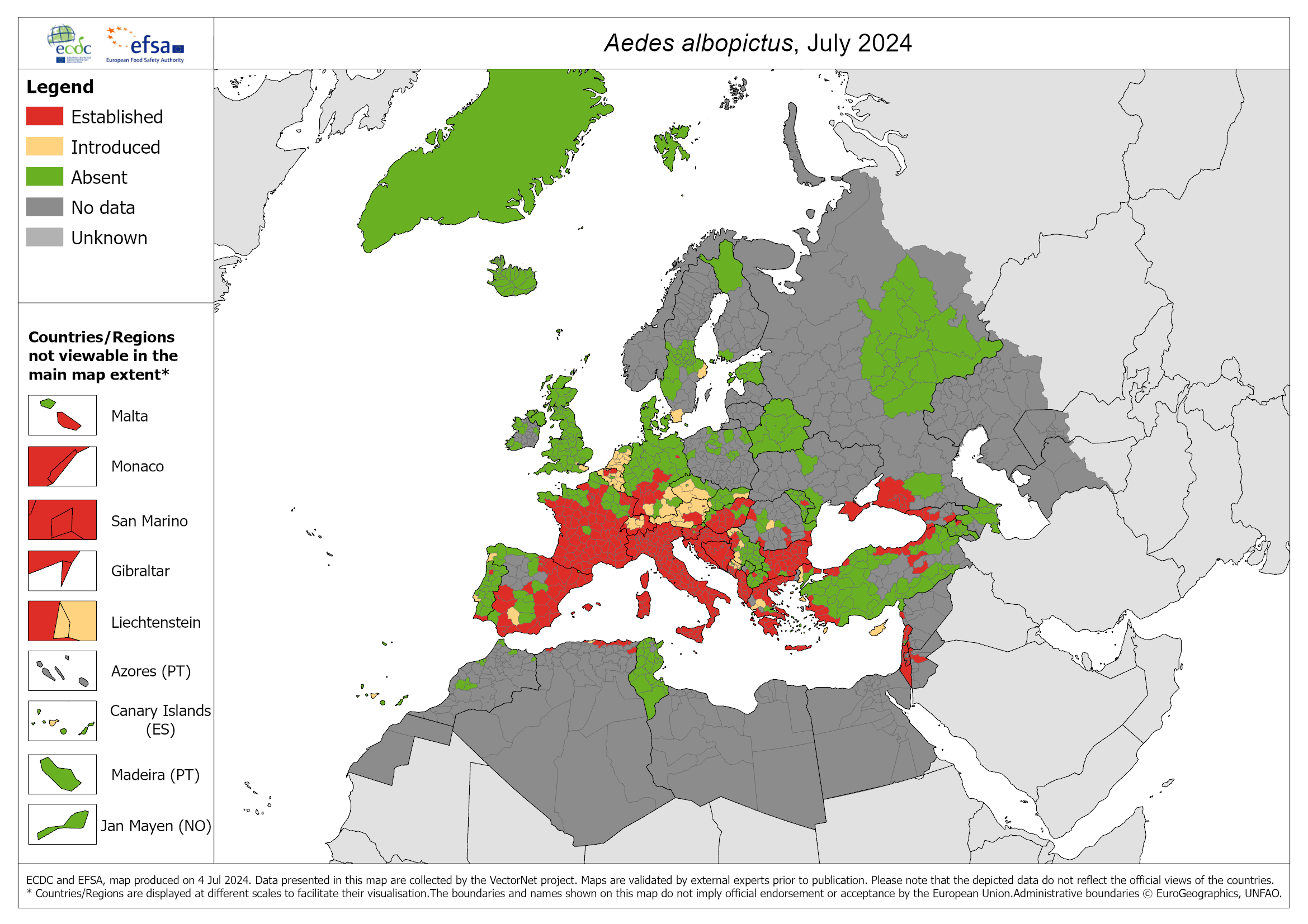

In 2023, a surge in local transmission of dengue was observed in Europe via Aedes albopictus.1 The tiger mosquito Aedes albopictus, native to the tropical forests of South-East Asia, is now found throughout the world, with the exception of Antarctica.12

In France, Aedes aegypti is present in the West Indies, Guiana and Mayotte, while Aedes albopictus is found on Reunion Island and in several mainland departments (78 since 1 January 2024).12

Maternal transmission

The primary mode of dengue virus transmission between humans is the mosquito bite.1 While transmission from a pregnant mother to her baby is possible, it is uncommon and the risk appears to depend on the timing of the dengue infection during the pregnancy.1

Transmission through products of human origin

The virus can, more rarely, be transmitted by transfusion or by cell or organ transplant.1,11

Symptoms and treament

Symptoms

The incubation period of dengue varies from one person to another.2 Most patients (50-90%) have mild or no symptoms and will get better in 1-2 weeks. If symptoms occur, they usually begin 4-10 days after infection and last for 2-7 days.1

The disease has different forms of varying severity. Depending on the clinical picture, the WHO classifies dengue into two categories: dengue with or without warning signs and severe dengue.2 The severity of the disease depends on the serotype of the infecting virus.2 Serotype 2 (DENV-2) is more likely to cause severe cases.2

High fever (40°C) is often accompanied by muscle and joint pains, anorexia, retro-orbital pain, nausea and vomiting, sore throat, headache and rash.1,2

In rare cases, dengue can be serious and fatal.1

Individuals who are infected for the second time are at greater risk of severe dengue1. Symptoms of severe dengue often occur after the fever resolves:1

- Severe abdominal pain

- Persistent vomiting

- Rapid breathing

- Bleeding gums or nose

- Fatigue

- Restlessness

- Blood in vomit or stool

- Being very thirsty

- Pale and cold skin

- Feeling weak

In this severe form (haemorrhagic dengue), patients experience pleural effusion (abnormal presence of fluid in the pleural cavity) with hypoalbuminaemia or hypoproteinaemia, as well as increased vascular permeability which can lead to haemorrhage, with or without shock syndrome.2* The majority of neurological complications are caused by serotypes 2 and 3.2

*a group of severe and rapidly progressing symptoms including fever, rash, dangerous fall in blood pressure, and multiple organ failure.

Treatments

There is no specific curative treatment for dengue. The focus is on treating symptoms.1,2 In addition to rest, patients should regularly drink plenty of liquids to combat dehydration in the event of diarrhoea and vomiting.2

Most cases of dengue can be treated at home with pain medicine.1,2 Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs such as ibuprofen and aspirin are avoided, as they may increase the risk of bleeding1,2. For people with severe dengue, hospitalisation is often necessary.1

After recovery, people who have had dengue may feel tired for several weeks.1

Prevention

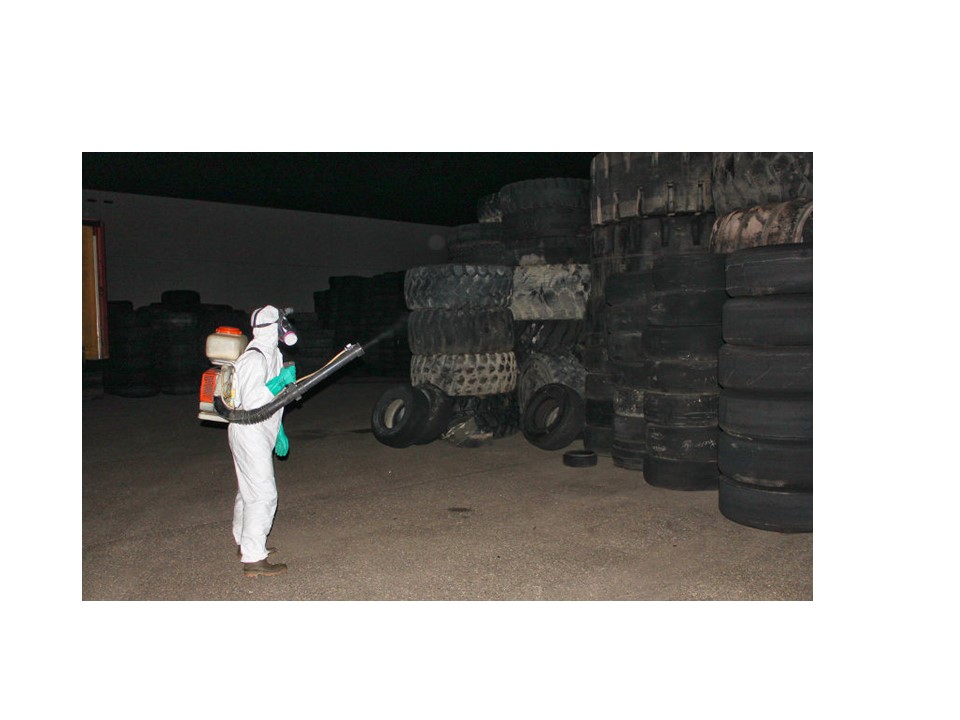

Vector control

Prevention is the best way to fight dengue. This involves fighting vector mosquitoes and deploying individual protection (mosquito repellent, wearing long and loose clothing, etc.). People living in an area likely to be affected by a dengue endemic or epidemic can help reduce this risk by destroying or drying out potential habitats – i.e. any reserves of stagnant water inside or outside the home.13

Dengue is a notifiable disease across mainland France and throughout the year. In the French overseas departments, there are specific systems for surveillance and reporting.14

The documents required to report a case of dengue (depending on the territory) are available on the Santé publique France website.

Vaccines

The fight against dengue also involves the development of a vaccine. The most advanced vaccines are all tetravalent and based on live attenuated recombinant viruses.15

Two vaccines are currently approved: Dengvaxia (Sanofi Pasteur) and Qdenga (Takeda).15

- Dengvaxia

Approved the first in 2015, Dengvaxia has shown 59.2% overall efficacy against dengue, with 80% efficacy against significant haemorrhagic dengue after the first injection and 88% after three injections.15 However, its efficacy varies according to serotype (50% against DENV-1; 35% against DENV-2; >75% against DENV-3 and DENV-4).15 It is also less effective in people who have never been infected (35.5%) than in those who have already had a primary infection (74.3%), and there is an increase in the occurrence of severe dengue in young children.2 It is also thought to be associated with an increased risk of severe dengue in vaccinated subjects who have never been in contact with the virus.2

This vaccine was withdrawn from the market on 31 March 2024.

- Qdenga

The efficacy of the second available vaccine varies by age group, serotype (69% against DENV-1; 90.8% against DENV-2; 51.4% against DENV-3 and 50% against DENV-4) and baseline serological status (74.8% for people with previous infection and 67% for those without previous infection).15 Overall efficacy is around 95% on severe forms of dengue; higher rates of efficacy are seen in people with a positive dengue serology and in the event of DENV-2 infection. No increased risk of severe forms has been reported.

The French National Authority for Health (HAS) recommends QDENGA vaccination for the following populations living in the French West Indies, French Guiana, Mayotte and Reunion Island:16

- children between 6 and 16 years of age with a history of dengue infection;

- adults between 17 and 60 years of age presenting with comorbidities, with or without a history of infection, given the risk of aggravation of these comorbidities by dengue.

The recommended vaccine regimen consists of two doses of QDENGA administered 3 months apart. This vaccination must be performed between two epidemics and at least 6 months after a dengue infection.16

Access the HAS recommendations (in French)

You can visit the HAS website to consult its recommendations concerning vaccination against dengue fever.

HASResearch: The actions of ANRS MIE

Arbo-France network

Placed under the aegis of ANRS MIE, Arbo-France is a French multidisciplinary and multi-institutional network for human and animal arboviral diseases, surveillance and research on the mainland and overseas territories.

Its main objectives are to:

- create an intelligence and alert system with ANRS EID,

- improve the visibility of arbovirus research in France and abroad,

- help with the set-up of research projects,

- provide scientific expertise.

LSDengue project

As part of the PEPR MIE 2023 call for proposals, ANRS MIE is funding the LSDengue project aimed at identifying the determinants of severe forms of dengue in order to define biomarkers for clinical use and adapt patient care. It envisages a study, the largest to date, of the comprehensive characterisation – clinical, genetic, virological and immunological – of hundreds of patients of diverse genetic origins, recruited from a large proportion of the geographical area of dengue incidence thanks to a vast network in the French overseas territories. This involves anticipating the progression of the infection to severe dengue, improving patient care and reducing the risk of infection-related mortality. This intercontinental network could provide a solid basis for the preparedness and control of emerging viruses, particularly arboviruses and dengue.

ARBOGEN project

Several elements suggest that the genetic determinants of dengue virus (genotypes and mutations) affect the severity of the disease. The aim of the ARBOGEN project, funded by a partnership between ANRS MIE and MSDAVENIR, is to study the role of these determinants. Given that the genetics of the virus may limit the effectiveness of diagnostic tests, generate resistance to antivirals or vaccine escape, genotype sequencing (DENV-1 to DENV-4) could help identify new therapeutic targets and markers to anticipate disease progression and adapt patient care to the ‘genetic profile’ of the circulating virus. Ultimately, research efforts should make it possible to quickly adapt epidemic countermeasures and reduce the burden of severe dengue.

This project is an opportunity to set up the first French trans-territorial network of public and private collaborators to collect DENV genomes from dengue cases in the French overseas and mainland territories. ARBOGEN is a network for sharing data on arbovirus sequences, which will constitute an excellent resource and beyond this project will serve as a basis for viral emergence preparedness.

Franco-Brazilian scientific cooperation

Drawing on their complementary areas of expertise, Brazil and France are mobilising to share their knowledge and develop joint projects on arboviruses, including dengue. On 30 and 31 October 2024, a Franco-Brazilian workshop on the theme of arboviruses was held in Belém (Brazil), organised by Instituto Evandro Chagas (Secretariat for Environmental and Health Surveillance, Ministry of Health of Brazil) and ANRS MIE, with the support of the French Embassy in Brazil and in partnership with the Arbo-France network.

References

- Dengue et dengue sévère. https://www.who.int/fr/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dengue-and-severe-dengue#:~:text=La%20dengue%20est%20une%20infection,d%27infections%20survenant%20chaque%20ann%C3%A9e. (consulté le 16/12/2024)

- Tinto B, et al. Circulation du virus de la dengue en Afrique de l’Ouest. Une problématique émergente de santé publique. Médecine/sciences 2022 ; 38 : 152-8.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. 12-month dengue virus disease case notification rate per 100 000 population, December 2023-November 2024. 12-month dengue virus disease case notification rate per 100 000 population, December 2023-November 2024. (consulté le 07/01/2025)

- Le rapport 2019 du Compte à rebours du Lancet sur la santé et le changement climatique. https://www.thelancet.com/pb/assets/raw/Lancet/Hubs/climate-change/TL_Countdown_ExecutiveSummary_French-1573659911007.pdf (consulté le 16/12/2024)

- Santé publique France. Dengue aux Antilles. Point au 15 novembre 2024. https://www.santepubliquefrance.fr/regions/antilles/documents/bulletin-regional/2024/dengue-aux-antilles.-point-au-15-novembre-2024#:~:text=Guadeloupe,depuis%20plus%20de%2020%20ans. (consulté le 16/12/2024)

- Harapan H, et al. Dengue: A Minireview. Viruses 2020, 12, 829; doi:10.3390/v12080829.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Local transmission of dengue virus in mainland EU/EEA, 2010-present. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/all-topics-z/dengue/surveillance-and-disease-data/autochthonous-transmission-dengue-virus-eueea. (consulté le 16/12/2024)

- Mes vaccins. Cas autochtones de dengue, chikungunya et Zika en Europe cette année 2023. https://www.mesvaccins.net/web/news/21518-cas-autochtones-de-dengue-chikungunya-et-zika-en-europe-cette-annee-2023. (consulté le 16/12/2024)

- gouv.fr. Moustiques vecteurs de maladies. https://sante.gouv.fr/sante-et-environnement/risques-microbiologiques-physiques-et-chimiques/especes-nuisibles-et-parasites/moustiques#:~:text=Depuis%20le%201er%20janvier,site%20de%20Sant%C3%A9%20Publique%20France. (consulté le 16/12/2024)

- Romanello M, et al. Le Rapport 2023 du Lancet Countdown sur la santé et les changements climatiques: l’impératif d’une démarche axée sur la santé dans un monde confronté à des dommages irréversibles. https://www.thelancet.com/pb-assets/Lancet/Hubs/countdown/translations/French_Lancet_Countdown_2023_Executive_Summary-1700054097183.pdf. (consulté le 16/12/2024)

- Santé publique France. Dengue. https://www.santepubliquefrance.fr/maladies-et-traumatismes/maladies-a-transmission-vectorielle/dengue/la-maladie/#tabs. (consulté le 16/12/2024)

- Le moustique tigre. Le moustique tigre | Anses – Agence nationale de sécurité sanitaire de l’alimentation, de l’environnement et du travail. (consulté le 16/12/2024)

- Ministère de la santé et de l’accès aux soins. Dengue. https://sante.gouv.fr/soins-et-maladies/maladies/maladies-vectorielles-et-zoonoses/article/dengue. (consulté le 16/12/2024)

- Ministère de la santé et de l’accès aux soins. La dengue : informations destinées aux professionnels de santé. https://sante.gouv.fr/soins-et-maladies/maladies/maladies-vectorielles-et-zoonoses/article/la-dengue-informations-destinees-aux-professionnels-de-sante. (consulté le 16/12/2024)

- Desprès P, et al. Le vaccin contre la dengue. Un défi scientifique majeur et un enjeu de santé publique. Médecine/sciences 2024 ; 40 : 737-47.

- HAS. Stratégie de vaccination contre la dengue. Place du vaccin Qdenga. Argumentaire. 5 juillet 2024. q348tr3dlkmsks91l46xj46vl1ff. (consulté le 16/12/2024)