Mpox

Mpox, formerly known as monkeypox, has been circulating for decades in West and Central Africa.

Last updated on 04 March 2024

In brief

Mpox, formerly known as monkeypox, has been circulating for decades in West and Central Africa. In 2022, for the first time, sustained human-to-human transmission was observed throughout the world, including France and elsewhere in Europe.

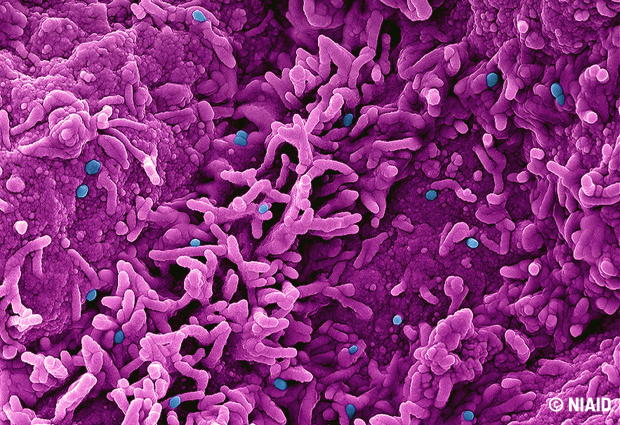

Identified in a laboratory monkey breeding facility in Denmark in 1958, the mpox virus was first detected in humans in the Democratic Republic of Congo in 1970. Since then the virus has been the cause of increasingly frequent outbreaks in West and Central Africa. The particularity of the outbreak that began in 2022 is related to its transmission through sexual contact, which had been rarely observed in previous epidemics. The disease manifests through a characteristic skin rash phase. The majority of patients recover spontaneously within a few weeks. Vaccines developed for smallpox can be used for mpox, as well as medications (tecovirimat and cidofovir). However, scientific knowledge of mpox is still incomplete, with the need for research projects in order to better understand and manage the disease.

Consult the Mpox Emergence Unit

Research priorities

Research priorities as defined by our agency include:

- Study of animal reservoirs: identification of the species responsible for spillover (when the virus crosses the species barrier, with transmission from animals to humans via rodents, bats, non-human primates, etc.) in endemic areas: risk and prevention of spillback (reverse-crossing of the species barrier, with transmission from humans to animals via companion animals, local wildlife, etc.) in areas with recent epidemic outbreaks.

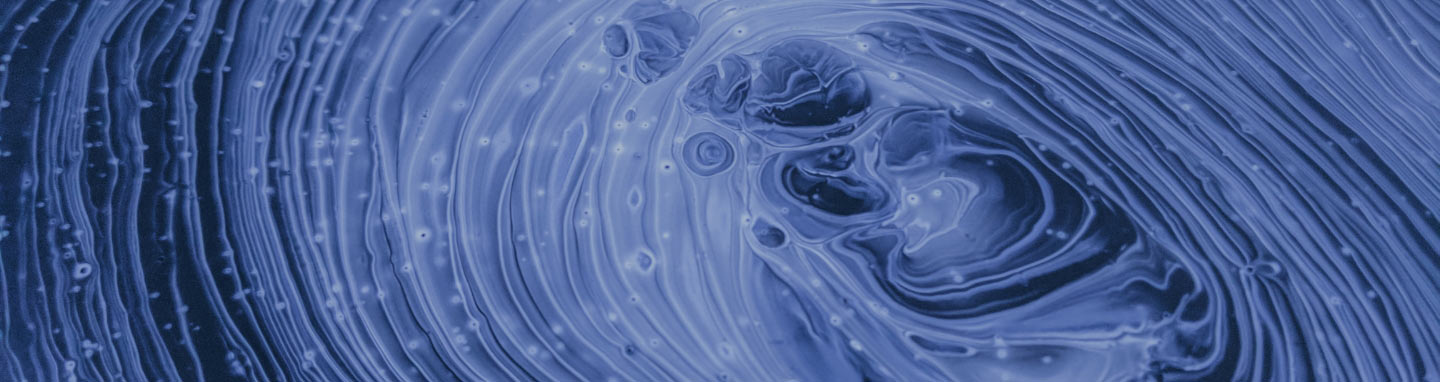

- Development of suitable diagnostic techniques: molecular, serological in humans and animals.

- Dynamics of virus circulation (in animals and humans) and modes of human-to-human transmission: seroprevalence, sexual transmission, droplet transmission, persistence of the virus in body fluids, duration of infectiousness, modelling studies to anticipate and guide public health policies.

- Natural history and pathophysiology of infection: virus/host interactions, pathogenesis, studies of virulence (role of mutations in pathogenesis), studies of immune responses.

- Human and social sciences research, particularly in the most vulnerable populations: analysis of the perception and understanding of the infection, socio-environmental factors of exposure, prevention and awareness-raising for vulnerable populations, perception of preventive measures, analysis of the dynamics of collective mobilisation, logics of the public authorities’ response.

Publications

- Gessain A, et al. Monkeypox. N Engl J Med. 2022.

- Ferré VM, et al. Detection of Monkeypox Virus in Anorectal Swabs From Asymptomatic Men Who Have Sex With Men in a Sexually Transmitted Infection Screening Program in Paris, France. Ann Intern Med. 2022.

- Thy M, et al. Breakthrough infections after post-exposure vaccination against Monkeypox. N Eng l J med. 2022.